The online advocacy video Kony 2012 can only be described as a digital enormity, breaking all records and rules. By one measure, it reached 100 million views in six days, fastest in the history of the web. But that’s only half the story. Other mega-popular videos have been entertainment (Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance”) or curiosities (“Charlie bit my finger”). They were short, snappy, and weird. Kony is an earnest 29-minute documentary about an obscure warlord in a forgotten corner of Africa: as unlikely a candidate for spontaneous mass popularity as can be imagined.

When a message goes viral, a good question to ask is whether it’s being propelled by the source of the message, its content, or the diffusion network. This scheme is a tad deceptive, because the categories tend to bleed into one another, but I find it useful in teasing out the dynamics of a viral message’s trajectory. With fair warning, I’ll employ it here.

The Source

Stephen King novels and Will Smith movies are examples of source-driven popularity. Plots and reviews scarcely matter. King and Smith, by their personal relationship with the public, have delivered an abnormally high number of blockbusters.

Invisible Children, which produced Kony, originally appeared to me to fall on the opposite end of the spectrum. The organization is composed of three young Southern California film-makers, led by Jason Russell, the video’s director and star. I had never heard of them, and I’m willing to bet most smart people on the East Coast had never heard of them either – and the few who did paid no attention. For many of us, the makers of Kony 2012 materialized from nowhere, along with their video and their cause.

This is an inaccurate impression. Since 2003, Invisible Children has been agitating with a fervor – and effectiveness – far exceeding its numbers. The group has reached out to schools, colleges, and churches, in the process assembling a network of volunteer supporters who were equally zealous in passing the word about the kidnapped children of Uganda. With their help, a previous video attained an audience of 5 million – a nontrivial achievement by any standard other than Kony’s.

For members of the network, Invisible Children were keepers of the flame – an attention-worthy source. The organization, by the same token, could count on a pre-assembled diffusion network, and could tailor content to its tastes.

The content

Because content is what goes viral, the natural tendency among pundits and the public alike is to assign to it the lion’s share of the credit. Kony 2012 is no exception: its content has received exorbitant praise and condemnation. Yet I suspect that new content by itself seldom has spontaneously “found” a new audience. The surprise popularity of Monty Python, an eccentric foreign program, might be an example of such a discovery, though we are on surer footing with freak web video hits like “Evolution of the dance.”

Kony’s content combines slick, cleverly paced production effects with a simple fairy tale-like story about the children of light who rescue the children of darkness. The fairy tale is perceived visually, while Russell, the narrator, intones idealistic pieties. I noted in my last post that Ethan Zuckerman and others have attacked the video’s “simplifications,” but its persuasive power, particularly for the young, must reside precisely in the stark division of moral domains, between the fortunate us and the tormented them.

Every advocacy message must contain an “ask”: some action required of the viewer. Kony’s are highly original and easy to accomplish. The public is asked to help “make Kony famous” by forwarding the video, putting up posters, and soliciting by means of social media the support of specific “culture makers” and “policy makers.” By these ingenious requests, the content, like a selfish gene, assists in its own replication.

My guess is that persuasiveness and originality played a small part in Kony’s viral run. An anatomical dissection of the documentary would uncover many more barriers than draws to popularity. The subject matter, for example, is unentertaining, unfunny, unsexy. The length far exceeds the attention span of the target audience. Those “asks” mentioned above appear 23 minutes into the video – by which time the average young viewer has moved on to Zelda and probably finished off a couple of levels.

It is a fact that Kony’s formal structure didn’t prevent it from going viral. We know that now, with the wisdom of hindsight. But nobody, lay or expert, would have predicted the video’s astonishing level of success before the fact simply by viewing the content: and that hasn’t changed.

The network

A network can be assembled informally, like the human web of activists from black churches and colleges who led the campaign against segregation in the South. The term can also apply to a company’s distribution apparatus: old Hollywood firms, we are told, were “vertically integrated giants with production studios, distribution networks, and theater chains.” The rise of the web in turn has engendered virtual networks, exploited by jihadi Islamists and fans of LOL Cats alike.

These categories bleed profusely into one another. It’s impossible to be virtual without being human. Mass media message-senders poach on amateurs, and vice versa. For any given message, the only hard requirement for membership in the diffusion network is willingness to spread the word, for love or money.

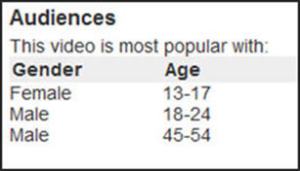

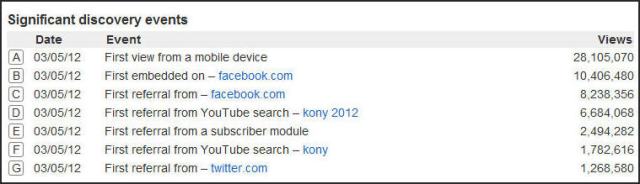

By preaching the anti-Kony message in schools and churches, Invisible Children had assembled a youthful community, which the video explicitly sought to activate. That it did so is beyond dispute. We get a broad fix on the demographics of this diffusion network from YouTube statistics for March 13: females aged 13 to 17 lead the charge, followed by males aged 18-14.  (In the third group, males aged 45-54, I’m tempted to see the Ethan Zuckermans of the world making sputtery sounds.) The dominant means of diffusion, predictably for this age group, were mobile phones, Facebook, and Twitter (where #StopKony trended for several days).

(In the third group, males aged 45-54, I’m tempted to see the Ethan Zuckermans of the world making sputtery sounds.) The dominant means of diffusion, predictably for this age group, were mobile phones, Facebook, and Twitter (where #StopKony trended for several days).

A deeper probe into the character of the Kony network begins to turn up surprises. Gilad Lotan parsed the first 5,000 posters to the #StopKony hashtag, and found they clustered around mid-sized cities in the South and heartland: Birmingham, Alabama; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Oklahoma City; Dayton, Ohio; Noblesville, Indiana. Lotan then produced a tagcloud from the user profiles of these vanguard posters. “We easily identify prominent words,” he writes, “such as Jesus, God, Christ, University, and Student.”

The early adopters of Kony 2012 reflected the work carried out by Invisible Children among church groups across the country. These were young people from Birmingham and Dayton rather than New York or Los Angeles, and Christian faith rather than political ideology was for many a motive for taking up the anti-Kony cause. It’s easy to see why eastern seaboard types first missed, then misunderstood what transpired.

Lotan touches on the success of Kony’s “attention philanthropy tactics.” Responding to the main “ask” of the video, young people in places like Noblesville and Pittsburgh – members of the network – generated a vast volume of social media communication, which aimed to persuade “culture makers” to endorse the cause. Several did, including Justin Bieber and Oprah Winfrey. Activation of the immense networks following these entertainers may well have driven Kony and its message above the “awareness threshold” – the point at which viral diffusion becomes self-sustaining.

Conclusion

The principle of uncertainty hovers around viral messages. Despite the hopes and wishes – and billions of dollars – of marketing departments, it’s impossible to predict when content will go viral. Duncan Watts has shown this conclusively. But it isn’t impossible to explain the effect, and there are good reasons to do so. A viral message is a probe sent into the deep space of the information sphere, allowing us a glimpse, however partial and brief, of the actions and predilections at work there.

Reflection on the facts behind the extraordinary popularity of Kony 2012 will lead, I think, to some counter-intuitive conclusions. Most observers (myself included) considered Kony an online apparition – a social media monster. Yet the dynamics of its explosive diffusion demonstrate the importance of face to face encounters in forging a community, and of shaping content with a keen understanding of community values. While “attention philanthropy” seems like a brilliant marketing gambit, it was the nature of the cause and the idealism of the youthful Konyites which persuaded celebrities like Oprah Winfrey to amplify the message. I doubt this approach could be duplicated commercially.

Pingback: Make Tweeting Famous | carlyboag

Pingback: https://thefifthwave.wordpress.com/2012/03… « eripsa

It’s Oprah Winfrey…

Pingback: Pause for the Cause – selfish genes, ethics and ghost ships | Almshouse

It’s also worth noting that Invisible Children had a sustained campaign in which thousands of kids camped outside the Oprah Winfrey Network headquarters in Chicago, culminating in Oprah dedicating part of one of her last show’s to the LRA, child soldiers, and Invisible Children. There has been so much groundwork for this, for years.

The network is also unique and remarkable in that it’s sustained by legions of volunteers — kids who raise money to live in a group house in San Diego (or live in a van) and work crazy hours for IC unpaid. There is a strong social milieu specific to IC that creates a fierce, black and white moralistic dedication I haven’t seen anywhere else. The culture pulls a lot from the culture of evangelical churches in southern California — edgy, hip, youthful and all over new media.

Those are excellent observations. I felt the video had an evangelical “come up and testify” feel to it, but didn’t know enough about the makers to tell whether this was consciously done.

Pingback: Das Claudoskop: Roboții pot sări sus. GPS spațial | Das Cloud

Pingback: Leveraging Communities for Social Media Success « IPSA @ Wagner

Hi Martin,

Your two posts on Kony2012 are amongst the most interesting I have read on this topic. Thanks.

My effort probably puts me in your category of ‘outraged gatekeeper”: http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/polis/2012/03/09/why-i-think-the-kony-2012-campaign-is-wrong/

(Though I have included a defence of the campaign on my blog, too.)

I think you are onto something around the idea that Kony2012 is about network not content, let alone source. I also think that Ethan’s ‘simplification’ criticism is too general. Just about all my journalism work (even my academic work!) has involved simplifying stuff.

But I think you perhaps ignore the message while looking at the medium. In the end I think the campaign is ‘wrong’ not because of its style, his messianic ego, the patronising neo-colonialism, etc.

I think it’s politically and practically wrong. I don’t think they will catch Kony and I think much harm will be done to long-term efforts to improve human rights and justice. Russell’s analysis is wrong. This is not a uniquely crucial time in history for Kony (or anything else). Awareness is not the answer either. Sending in US shock troops doesn’t have a great track record either.

Thanks again for your writing on this, it’s been very helpful,

regards

Charlie Beckett

(LSE)

Thanks, Charlie. Well, you do sound like a gatekeeper. Part of the Fifth Wave environment we now face includes individuals who, in essence, pursue their own foreign policy – and possess the communications tools to have a state-like impact. Julian Assange is one, for example. As a crusty former US government person, I think he’s wrong, but there he is. Just the same with Jason Russell. The salient point, I think, isn’t whether he’s right or wrong from my (or a government’s) perspective, but rather that he has been able to persuade so many millions of the virtue of his own private-public pursuits.

That was not possible 20 years ago. It’s becoming increasingly frequent today.

Pingback: 2019: The year revolt went global | the fifth wave